The Varnas

There is a famous verse from the Rig Veda entitled Purusha Sukta, which describes how this physical world emanates from the cosmic body of God, or according to another interpretation, how the physical world is the body of God. This hymn describes, for example, how the moon arises from the mind of God, how the sun comes from the eye of God, how the mountains are His bones, and the trees and grasses are His hair, and so on. It also describes the human social body as an emanation from this same cosmic body. According to this hymn human society is divided into four social grouping called varnas. The word “varna” literally means “color” or “hue.” These four “colors” of men, therefore, represent universal psychological types of mankind. The divine head of this cosmic body becomes the priestly (brahmana) class, the arms of this body become the warrior (kshatriya) class, the stomach, or sometimes the thighs, become the agricultural or merchant (vaishya) segments of society, and finally, the feet of this cosmic form become the worker (shudra) segments of society. In this way, human society is directly related to the cosmic body of the universe. Maintaining the social order is maintaining the cosmic order. This is an act of dharma.

The Ashramas

In addition, to these four varnas, the later Smriti Vedas add yet another layer to this system, namely four stages of life called ashramas. As the varnas divide the social body, the ashramas divide the life of an individual. Assuming the life of a human being is 100 years, each stage is afforded 25 years. The first quarter is called the student phase (brahmacharya). During this time of life the individual goes to the home of the guru (guru-kula, the ancient Sanskrit word for school) and lives a life of celibacy serving the teacher and learning what needs to be learned for later years. After graduation the student adopts the next stage of life, the householder (grihastha) stage and takes on worldly responsibilities, which include wife, family and career. By age fifty it is recommended that the householder turn his mind back to the ways of spiritual life as in younger days and so moves into the retirement (vanaprastha) stage of life. In this stage he passes household responsibilities over to his children, leaves home and enters the forest (vana) to be away from the world. Husband and wife remain together, but in a more renounced way. The vanaprastha stage is the gradual winding down of material affairs in preparation for the final stage, complete renunciation or sannyasa. In this final stage of sannyasa a man will send his wife back to his family, symbolically perform his own funeral rites and spends his remaining days as a monk seeking final release (moksha) from the world. This was the model.

Together these two systems of varnas and ashramas are known as Varnashrama Dharma, the ancient social system that was meant to assure spiritual and material prosperity for both society and the individual. The Bhagavad Gita, which is part of the later Smriti Veda, speaks of the varnas as being created by God according to an individual’s qualities and actions and not according to birth. There are many verses that describe the qualities and responsibility of each varna. In other words, an individual’s varna was to be determined by one’s psychological disposition and activities and not one’s birth. For example, an individual who was naturally peaceful, gentle, studious, clean and non-violent had the potential to become a member of the brahmana class. Someone with the qualities of bravery, resourcefulness and leadership had the potential to be a warrior or kshatriya. A person with a natural inclination to do business would be considered a member of the vaishya community, and finally a person without qualities of these three “higher” varnas would be placed as a member of the laboring class and could work for the three higher varnas. In this way, the system of varnas placed individuals in positions that best suited their psychological makeup, and the system of ashramas maintained the spiritual focus of society. This at least was the theory. Reality, however, was quite different.

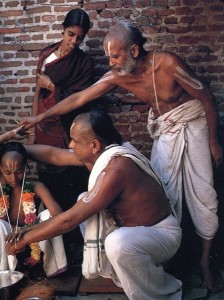

The Caste System

The traditional Hindu caste system, although taking its inspiration from the system of Varnashrama Dharma, is based solely on birth and not qualities or action as mention in the Gita. The son of a priest became a priest regardless of his qualities or activities; the son of a warrior became a warrior regardless of his bravery or leadership qualities. The son of a merchant became a merchant regardless of his business abilities. In fact, temple priests of a certain sect formed their own subdivision within this system; priests who did funerals formed another subdivision. There were even brahmanas who became cooks and so formed their own subgroup. Similarly, kshatriyas of different grades distinguished themselves from other kshatriyas; within the business community gold merchants, for example, distinguished themselves from grain sellers, land owners distinguished themselves from other members of the vaishya community, and in this way, the Hindu caste system divided society into a complex array of subgroups (samajas and jats) according to job divisions and birth rights. This was analogous to guilds of ancient Europe.

The traditional Hindu caste system, although taking its inspiration from the system of Varnashrama Dharma, is based solely on birth and not qualities or action as mention in the Gita. The son of a priest became a priest regardless of his qualities or activities; the son of a warrior became a warrior regardless of his bravery or leadership qualities. The son of a merchant became a merchant regardless of his business abilities. In fact, temple priests of a certain sect formed their own subdivision within this system; priests who did funerals formed another subdivision. There were even brahmanas who became cooks and so formed their own subgroup. Similarly, kshatriyas of different grades distinguished themselves from other kshatriyas; within the business community gold merchants, for example, distinguished themselves from grain sellers, land owners distinguished themselves from other members of the vaishya community, and in this way, the Hindu caste system divided society into a complex array of subgroups (samajas and jats) according to job divisions and birth rights. This was analogous to guilds of ancient Europe.

It is certainly beyond the scope of this primer to examine the Hindu caste system in more detail other than to ask: How is modern Hinduism in the West related to this ancient system of castes or even varnas and ashramas. The answer is simple: modern Hinduism is not dependent on either of these ancient systems. There is no theological or philosophical imperative that demands that modern hinduism conform to these ancient systems. In fact, much of what naturally results from these hierarchical systems would be illegal in a modern democracy. There are special rights and privileges that are awarded to the different varnas that could not be permitted in a modern democracy. It is to the credit of hinduism that it has detached itself from its traditional caste system. This shows its ability to adapt to modernity and the West.

There are, however, some areas where the ancient caste system still operates within modern Hinduism. One is in the area of marriage, another is in the area of work, and the other is in the area of temple priests. Hindu families that are traditionally brahmanas, for example, and who prefer to see their children marry other brahamanas, create brahamana social groups (samajas) to promote and maintain brahamana values. They especially create data bases of prospective marriage partners within the same brahmana caste. In a similar manner, there are merchant groups amongst traditional vaishya families that seek to promote marriage and business relations within the same traditional castes. Within these business communities they will also share business opportunities and employment within their own group to the exclusion of outsiders, including Hindus from other parts of India. And finally, a Hindu temple will generally only hire a traditional caste priest to serve as a temple priest. Hindu congregations generally will only accept a traditional caste priest. They will not accept even one of their own members, who may be extremely devoted, to serve even as an assistant on the altars if they are not from traditional caste brahamana families.

I do see, however, how a general understanding of the original system of varnas and ashramas can serve as a guide for child development and personal spiritual growth. Understanding the psychology of a child can certainly help guide a child into an occupation that suits his or her personal psychology. In other words, the varna model applied to child psychological development can be beneficial. Forcing the son of a doctor to become a doctor when the child may be better suited to perform another occupation, just for the sake of money or family status, has been a prescription for rebellion and unhappiness. We see this within our Hindu communities. Similarly, applying aspects of the ashrama system with its emphasis on spiritual growth can also have beneficial results.