Hinduism, like other religions, has many religious groupings. The Sanskrit word for this is sampradaya, which comes from the verbal root “da” meaning to “give.” A sampradaya therefore is something that is “given” or passed down from generation to generation. Hence, the idea of a religious tradition. In Christianity the equivalent of sampradaya is denomination.

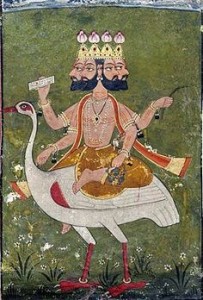

In general terms Hinduism breaks down into four broad religious groupings or sampradayas determined mainly by which Deity is the major object of worship. There are Shaivas who focus on Shiva, Vaishnavas who focus Vishnu, Shaaktas who focus on a female form of Divinity, and an almost endless number of folk traditions. The expression “folk traditions” is a catchall phrase to mean the huge number of local traditions that pervade every part of Hinduism and which commonly intermix with the Shaiva, Vaishnava and Shaakta traditions. Each of these major groupings can be called a sampradaya, but even more so, within each of these major groupings there are many sub-groupings that can also be called sampradayas. Amongst the Shaivas, for example, there are Kashmiri Shaivas, the Shaiva Siddhanta, and the Vira Shaivas, and so on. Amongst the Vaishnavas there are Shri Vaishnavas, Madhva Vaishnavas, and Caitanya Vaishnava, and many others. In this way, we can speak of each major grouping as a sampradaya as well as each sub-grouping as a sampradaya. If we compared this to Christianity, it would be somewhat similar to saying, Christianity is divided into three major groupings, the Catholic, Orthodox and Protestant traditions and within each of these major groupings are many sub-groups. Amongst Protestants, for example, there are Baptists, Methodists, Anglicans, Quakers, and so on. All of these major groupings and sub-groupings are the “sampradayas” of Christianity, which they call denominations.

Within Hinduism the sampradaya is similar to the tree model of religion. Elsewhere we spoke of different models of religion, namely the tree and the river models. We described Hinduism as a river, distinct from most other religions that follow a tree model of religion. The sampradaya is akin to the tree model of religion. Most of the sampradayas of Hinduism start from a source, a major philosopher or guru. Ramanuja is the founder of the Shri sampradaya of Vaishnavas, Madhva is the founder of Madhva Vaishnavas, and so forth. Similarly Shankara is the founder of a major sampradaya of Hinduism called Advaita Vedanta. In this way we can say the within the river of Hinduism there are many religions. This is the sampradaya.

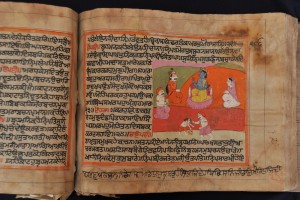

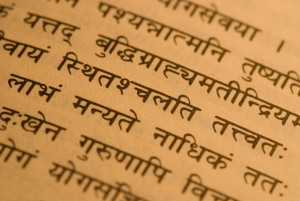

s are in the form of written documents, scripture. Given this fact, one could argue that what scripture actually is are voice sounds and words on paper, or more likely today, digital code and marks on a computer screen. In this sense, scripture is not different from any common dialogue or piece of writing. But we know there is a world of difference between scripture and a common newspaper or a novel. Scripture is sacred. Newspapers and common novels are secular. It is therefore, the quality of “sacredness” that creates the difference between scripture and an ordinary piece of writing.

s are in the form of written documents, scripture. Given this fact, one could argue that what scripture actually is are voice sounds and words on paper, or more likely today, digital code and marks on a computer screen. In this sense, scripture is not different from any common dialogue or piece of writing. But we know there is a world of difference between scripture and a common newspaper or a novel. Scripture is sacred. Newspapers and common novels are secular. It is therefore, the quality of “sacredness” that creates the difference between scripture and an ordinary piece of writing.