In common usage, a rishi is a word that simply means an inspired poet or sage or a holy person in general. In more specific usage the rishis are semi divine beings distinct from gods (devas), demons (asuras) and men who “heard” the Vedic hymns and passed them on down to mankind. In fact each sukta or hymn of the Veda is associated with the name of one of these rishis. The rishi are the patriarchs and progenitors of mankind. In the ancient texts 10 original rishis are mentioned who then become the source for the Hindu gotra lineages. Seven of these ancient and divine “seers” have been immortalized in the heavens. The Sapta Rishis, the seven sages, is the Hindu name for the Big Dipper (Ursa Major) in Hindu astronomy. Each star of the Big Dipper is named after one of these rishis.

A Note about Western Perceptions of India

Hindu Diversity

Whole books have been and could still be written on the topic of Western perceptions of India, but here are just a few things that regularly come up in my dealings in the West between Hinduism and the Westerners. First, Westerners tend to look upon India as if it was just one thing. They fail to see the huge diversity that exists within India. India is more diverse than Europe. The differences between Bengal, for example, and Gujarat, two Indian states, one in the east and the other in the west, are more diverse than between Germany and England. The Germans and the English at least share a similar writing system. Bengalis and Gujaratis have different alphabets. Similarly, the differences between North India and South India are even greater. The ways of worship, the ways of food, the ways of a marriage are vastly different between the North and the South. Westerners should be aware of the huge diversity within India and Hindu culture in general.

The West is Materialistic/India is Spiritual

The second misperception is that India is spiritual and the West is materialistic, but this is simply not true. There is a great hunger within India and within Indians in the West for modernization and for all the material goods of a modern world. Hinduism has no problem adapting to modern technology or dealing with modern science and using these things for all the pleasures of life. In fact Hindu culture has a great tradition of so-called secular advancement. There is nothing exclusively spiritual about Indian culture. Indian culture is a mixture of spirituality and materialism. On the other hand, there is nothing inherently materialistic about the West. The roots of Western culture are profoundly spiritual. Judaism, Christianity and Islam, the three pillars of Western culture, have grappled with the deepest spiritual questions and what we have today in the West with all its so-called materialism is a culture that is still grounded in deep spirituality. My point is this, both Hinduism and the Western traditions are neither exclusively one or the other. They both are ancient traditions that attempt to express the aspirations, hopes and dreams of humanity with all its spirituality and its material ambitions. There are indeed differences between the two traditions, but for a Westerner to think that the West is materialistic and India is spiritual is a great mistake.

Exotic Hinduism

And finally, when Westerners come to Hinduism they tend to be attracted to the more mystical and exotic sides of the tradition. Meditation and kundalini yoga come to mind, but your average Indian Hindu practices a kind of Hinduism that is more like what the average Christian practices. Most Hindus are just “normal” people who work during the week and come to a temple to pray on the weekends. Exotic mediation and raising serpent powers through chakras is far from their minds. Most of what is practiced as Hinduism in the West by Indians is more like the religion of the average Christian than the exotic forms of Hinduism that many Westerners seek. Sensing this hunger for exoctic forms of Hinduism there are many Indian “gurus” who come to the West in order to “cash in” on the lucrative Western market for exotic spirituality. Westerners should be aware that there is a lot of cheating going on in the guru market.

Hinduism and Science

The relationship between Hinduism and science is not easy to describe. Since Hinduism has no centralized ecclesiastical authority, no “church” as it were, it is impossible to get an official position on science or any other issue. In the case of Christianity one can get the official Roman Catholic position on science, and similarly one can get official Lutheran or Baptist positions on evolution, on capital punishment, abortion, birth control, and so on, but this is not the case with Hinduism. Individual Hindu groups (sampradayas) may have official positions determined by a guru, but in general, there are no large organizations that speak for major segments of the tradition. Consequently, we can only address the relationship between Hinduism and science in the most general of terms.

What we can say, is that Hinduism, like Christianity, Judaism and Islam is a metaphysical system. Science, on the other hand, is non metaphysical and so accepts no divine or “outside the system” source. In this way, Hinduism stands along side the major theologies of the world in its relation to science. That Hinduism has a polytheistic side, unlike Judaism, Christianity and Islam, matters little when it comes to the issue of science. The key point is that Hinduism is a metaphysical tradition, whereas science is not.

In many ways the relationship between science and religion can be determined by how the members of a particular religion view scripture. And as might be expected, within Hinduism, there are conservative Hindu views, modern liberal views and everything in between. Conservative Hindus accept the Vedas as the direct revelation of God and therefore inerrant. Whatever is stated in the Vedas, even if it is contrary to reason, sense perception and modern science, must be accepted. This is religious fundamentalism. On the other hand, there are Hindus who admit the Vedas contain much that is spiritual, yet they also think the Vedas are not infallible and so those parts of the Vedas that contradict reason or science can be rejected. This is religious liberalism, and it involves a high degree of rationalism and secularization. And finally there are Hindus, the mass majority of whom, accept the Vedas contain divine revelation, but think such revelation is not free of errors because the Vedas have been written and interpreted by human beings who are flawed and conditioned by their place history. Consequently, those parts of the Vedas that seem out of step with reason and proven science are not to be rejected, but must be reinterpreted in a way that conforms to reason and, ultimately, science. All three of these approaches fall within the realm of what, in theology, is called hermeneutics or the interpretation of sacred writings. Indeed, all religions have adherents who subscribe to one of these basic modes of scriptural interpretation and therefore their views towards science follows one of these three general modes.

Here is an example of how an important Hindu scripture, the Bhagavad Gita, might regard modern science. There is a chapter of the Gita entitled, Saankhya Yoga. The word “sankhya” means “counting,” “enumeration,” or “analysis.” In the Gita there is a simple form of “analysis” that classifies matter into eight constituent elements: earth, water, fire, air, space, mind, intelligence and ego. This is essentially a periodic table and an excellent example of early science or what used to be called natural philosophy. Even before the Gita, Hindu thinkers had taken this theme of “counting” and developed it into one of the six traditional philosophies of ancient India called Saankhya. From the perspective of Bhagavad Gita, it is fair to say that modern science is simply a highly detailed analysis of matter and so, in this sense, there is no conflict between the Gita and science. Modern science is simply more of what ancient Hindu thinkers had been doing for millennia, but where the Gita would disagree with modern science is that modern science does not go far enough in its analysis of reality. Vedic “science” is not simply about the mere analysis of matter, but it also includes the analysis soul and God. In other words, it includes metaphysical reality as well as physical reality. The sankhya of the Gita, therefore includes an analysis of physical reality as well as a spiritual reality. At present, modern science only accepts physical reality as its domain of study, but the call from the Gita is that ordinary science should also explore the metaphysical dimensions of life and so become a complete form of sankhya. But an objection can be made that science does not need to include such metaphysical issues as the soul and God because philosophy and theology already do this. I think the answer from the Gita would be that physical reality and spiritual reality are ultimately inseparable, and therefore, any study of one that omits the presence of the other will create a false or incomplete body of knowledge. Therefore even such non physical sciences as psychology, biology, or the medical sciences must include at least the premise that at the heart of reality there is a spiritual foundation, and even though we may not be equipped to see it at this point, it is there nonetheless and must be accounted for.

This simple example illustrates how, from a Hindu perspective, religion and science are related, but of course, most modern scientists, at present, would be hard pressed to include metaphysics within their scientific perspective and methodology. From a Hindu perspective, modern science is a legitimate, but incomplete, step towards knowing and understanding reality. From a modern scientific perspective, Hinduism goes too far in its assumption of what constitutes the foundations of reality and the means of knowing this reality. The relationship between Hinduism and science is, therefore, mixed. On the one hand, the basic approach of science can be accepted, but when it comes to the acceptance of metaphysical elements of reality the Gita and the Vedas embrace these principles as essential to the pursuit of truth. Current science cannot.

This simple example illustrates how, from a Hindu perspective, religion and science are related, but of course, most modern scientists, at present, would be hard pressed to include metaphysics within their scientific perspective and methodology. From a Hindu perspective, modern science is a legitimate, but incomplete, step towards knowing and understanding reality. From a modern scientific perspective, Hinduism goes too far in its assumption of what constitutes the foundations of reality and the means of knowing this reality. The relationship between Hinduism and science is, therefore, mixed. On the one hand, the basic approach of science can be accepted, but when it comes to the acceptance of metaphysical elements of reality the Gita and the Vedas embrace these principles as essential to the pursuit of truth. Current science cannot.

Consequently it is fair to say that the Hindu view of science is not that it is wrong, but that it only offers a limited view of reality. Until science is able to open itself to the exploration of metaphysical reality, it will remain incapable of understanding the full nature of reality. In general, the middle and liberal sides of Hinduism are favorable and open to science. The conservative sides of Hinduism, however, will remain closed to science. Interestingly, I see the gradual acceptance of a metaphysical view of reality by modern science an increasing possibility as more work is done in “cutting edge” areas of research like quantum mechanics, particle and string theories, cosmology and other areas that seems to point to answers that go beyond the common mechanistic view of the universe. It will be exciting to watch and see where these new theories lead.

Consequently it is fair to say that the Hindu view of science is not that it is wrong, but that it only offers a limited view of reality. Until science is able to open itself to the exploration of metaphysical reality, it will remain incapable of understanding the full nature of reality. In general, the middle and liberal sides of Hinduism are favorable and open to science. The conservative sides of Hinduism, however, will remain closed to science. Interestingly, I see the gradual acceptance of a metaphysical view of reality by modern science an increasing possibility as more work is done in “cutting edge” areas of research like quantum mechanics, particle and string theories, cosmology and other areas that seems to point to answers that go beyond the common mechanistic view of the universe. It will be exciting to watch and see where these new theories lead.

There is another relationship between science and religion that is current, but which, in my opinion, is a wrong attempt to link Hinduism and modern science. This is the attempt to read into the Rig Veda and other Hindu religious texts allegorical renderings that contain so called secret or vague references to modern ideas such as particle theory or quantum mechanics. I have seen interpretations by modern Hindus that attempt to show how modern particle theory was known at the time of the Rig Veda, and how this knowledge was secretly inserted into the text of the Vedas. I have seen attempts by modern Hindus to rationalize and reinterpret Puranic cosmology, which holds a geocentric view of the universe and describes the sun as closer to the earth than the moon, to name just a few differences, in terms of modern astronomy. As we have mentioned, from a Hindu perspective, there is no problem in exploring the possible religious implications of quantum mechanics, string theory or any other modern scientific theory that may open the way for modern science to explore a metaphysical view of the universe, but to read such theories back into the pages of the Vedas in order to justify faith or with so called Hindu nationalistic (Hindu-tva) motivations is not science at all. I caution my readers to be aware of such extreme reinterpretations of sacred writing.

Religious Marks: Tilaka/Tika

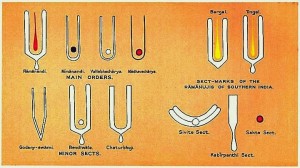

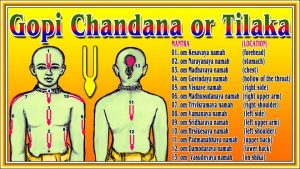

Going hand in hand with religious denomination (sampradaya) are the religious marks worn by the devotees of the the various schools of Hindu theology. These marks are called tilaka, or in Hindi and many other regional languages, tika. The tilaka is a religious mark worn mainly on the forehead and is made primarily of sandal paste, clay, or ash. The word tilaka is literally a “freckle” or “spot” and it is considered highly auspicious to wear these marks. In general, there are three broad categories of tilaka marks, those worn by Vaishnavas, those worn by Shaivas and general marks. Tilaka marks are made with white, red, yellow or black colors. Vaishnava marks run vertically on the body and Shaiva marks run horizontally. The Vaishnava tilaka is the most extensive. A trained observer can tell exactly which school of theology a devotee is coming from by the color and shape of these tilaka marks. It is fun to visit a traditional holy place of pilgrimage during festival season to watch the holy men and try to read their tilaka and determine which sampradaya they are representing.

In general Shaiva tilaka is made of ash coming from burned wood, cow dung or incense. The tradition of ash goes back to stories that tell how Mahadeva (Shivaji) would smear his body with ash taken from a cremation site, and so today, Shaivas mark their bodies with holy ash. In general, amongst Shaivas, the wearing of tilaka is not as extensive or as rigid as it is in the Vaishnava schools. Here are the most common Shaiva pattern.

By far the Vaishnava tilaka is the most extensive. Each school of theology, including all the sub-sects, have their own configurations. In the modern world the wearing of tilaka was two functions, general religious identification and personal sanctification. Nowadays, the need to distinguish sectarian differences is no longer relevant. Amongst the Vaishnavas there was a time when it was considered “sinful” to wear Shaiva tilaka or to even see it. In the past the different schools of theology aggressively debated with each other over the correctness of doctrine and so, like a sports team today, the tilaka was used to identify which school the debater was representing. At one time Madhva Vaishnavas were antagonistic toward Advaita Vedanta Shaivas. Shaiva kings hunted down and even persecuted Shri Vaishnavas. Shaivas would not enter Vaishnava temples and Vaishnavas would not go near Shaiva shrines. But today such sectarian differences hardly exist, and so we see both Shaiva and Vaishnava shrines within the same temple. The function of tilaka has changed greatly. In the West only priests generally wear tilaka and consequently the main function of tilaka is to distinguish a priest from the lay community. This function is similar to how a male Christian priest may wear a collar to distinguish himself from his congregation.

The other function of tilaka is for personal sanctification. Tilaka is generally applied to the body in twelve places (the number varies) after bathing. These places include the forehead, the throat, the heart, the stomach, two shoulders, arms, and so on. Each time a mark is applied, the name of a particular Deity is recited. This touching, marking, and evocation has the effect of personal sanctification. A priest is dedicating his body as a temple of God by applying tilaka.

- « Previous Page

- 1

- …

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- …

- 33

- Next Page »